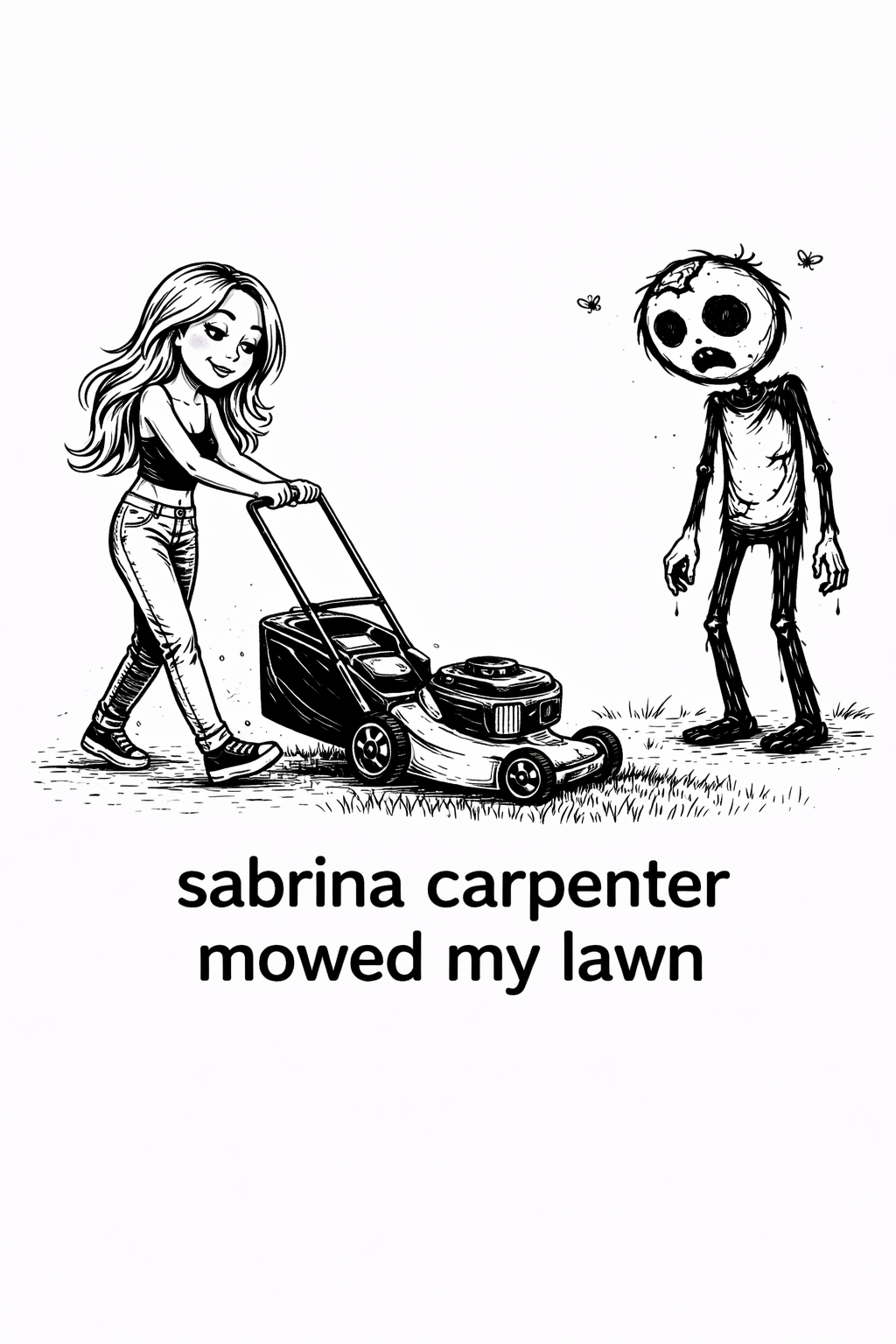

Sabrina Carpenter mowed my lawn

You probably woke up today, opened your phone, and saw at least one headline announcing that a celebrity had “broken the internet.” Maybe it was an actor who wore something unexpected. Maybe it was a musician who said something mildly controversial. Maybe it was someone simply existing in public. Whatever the event was, the reaction was outsized, immediate, and oddly unanimous…as if millions of people silently agreed that this moment mattered.

And that raises a simple but uncomfortable question: why? Celebrities feel important because we treat them as important. That’s not a moral judgment; it’s a description of how the system works. Celebrity doesn’t exist independently of attention. It isn’t a natural phenomenon. It doesn’t emerge the way gravity or weather does. Celebrity is an agreement, one that doesn’t require signatures, meetings, or official consent, just participation. Strip away the attention, and a celebrity is just a person with a job. Often a well-paid job, sometimes a very visible one, but still a job. Without cameras, headlines, and collective interest, the distinction disappears quickly. The difference between a movie star and someone buying groceries isn’t essence; it’s context.

Sociologists have been pointing this out for decades. Cultural theorists often describe celebrity as a social construct, something created and sustained by collective belief. Attention doesn’t just observe fame; it produces it. If millions of people stop watching, reading, clicking, and sharing, celebrity dissolves. Not slowly. Almost immediately. That doesn’t mean celebrities are fraudulent or talentless. Many are skilled performers, athletes, or creators. But skill alone doesn’t create celebrity. Plenty of talented people remain anonymous. Celebrity requires amplification. It requires systems designed to focus attention on a few individuals until familiarity feels like significance. That amplification doesn’t happen accidentally. Modern celebrity is manufactured through an intricate ecosystem of publicists, managers, agents, stylists, photographers, editors, algorithms, and platforms. Each plays a role in shaping how a person appears, what stories are told, and which moments are elevated into “news.” Media critics often compare this process to stage magic. You’re meant to see the illusion, not the machinery. Carefully timed interviews. Strategic vulnerability. Curated spontaneity. Even moments framed as “authentic” are often rehearsed versions of authenticity, relatable but controlled.

The glossy magazine profile where an actor insists they’re “just a normal person” who loves pizza and sweatpants is rarely spontaneous. It’s a narrative choice. Not necessarily false, but selected. Emphasized. Polished. The goal isn’t accuracy; it’s resonance. The story has to feel human enough to invite identification while remaining aspirational enough to maintain distance. That balance is crucial. Celebrity relies on familiarity without intimacy. You’re meant to feel like you know them, but never actually do. That illusion fuels one of the most distinctive features of modern celebrity culture: parasocial relationships. Psychologists use the term “parasocial” to describe one-sided emotional bonds people form with public figures. These relationships feel personal, even though they’re not reciprocal. You know their face, their voice, their habits. They don’t know you exist. And yet the emotional response is real.

Parasocial relationships aren’t inherently unhealthy. Humans are wired to connect through stories, faces, and repeated exposure. But the scale matters. When millions of people invest emotional energy into the lives of people they’ll never meet, attention becomes a commodity, and celebrities become vessels for projection. That’s why people often know intimate details about celebrities while remaining disconnected from those physically around them. The neighbor becomes background noise; the celebrity becomes narrative. One is unscripted and unpredictable. The other is packaged, edited, and endlessly available. What complicates things further is how much of celebrity identity is constructed. Public images shift rapidly. Someone is framed as charming, then troubled. Relatable, then out of touch. Admired, then scrutinized. These shifts don’t always reflect real changes in the person. They reflect changes in the story being told about them. Media historians often point out that celebrity culture functions like serialized fiction. Characters develop arcs. Conflicts emerge. Redemption is possible. Downfalls are inevitable. The audience consumes it not as documentation, but as entertainment. Facts matter less than momentum. That explains how someone can go from “beloved icon” to “problematic figure” almost overnight. The narrative changes, and the public follows. The person remains largely the same. The framing does not.

In that sense, celebrity culture says more about audiences than celebrities. The attention we give reveals our values, anxieties, aspirations, and boredom. We elevate certain traits at certain times. We punish others. We reward vulnerability, then demand privacy. We crave authenticity, then critique it when it doesn’t align with expectations. The system isn’t controlled by celebrities alone. It’s co-created. Publicists and platforms may guide the process, but attention completes it. Every click, share, comment, and outrage cycle reinforces the hierarchy. Celebrity exists because people participate in it, even when they claim to dislike it. That’s where the illusion becomes uncomfortable. Celebrity feels inevitable, but it isn’t. It persists because it’s engaging, distracting, and emotionally efficient. Following celebrity stories requires little effort and offers immediate payoff, drama, connection, validation, escape. In a fragmented, overstimulated world, that efficiency matters.

At the same time, celebrity culture subtly distorts perspective. It inflates the importance of individual actions while obscuring broader systems. It personalizes issues that are structural. It encourages comparison with lives that are heavily curated and financially insulated. It frames success as visibility rather than impact. None of that means celebrity should disappear. It means it should be understood. When something is understood, it loses its grip. The moment you recognize celebrity as a constructed phenomenon rather than an inherent status, its power changes. Celebrities aren’t superior beings. They aren’t moral authorities by default. They aren’t representative of universal experience. They are people who happen to occupy a highly visible position in a system that rewards attention. That position comes with privileges and pressures, benefits and distortions.

The irony is that many celebrities are keenly aware of this. They know the attention is conditional. They know the narrative can shift. They know that visibility is both currency and liability. The stability comes not from being seen, but from being seen favorably, which is always temporary. When someone “breaks the internet,” nothing actually breaks. Servers hum along. Life continues. What breaks is perspective. For a moment, collective attention narrows so tightly that a minor event feels monumental. And then, just as quickly, attention moves on. That impermanence is the quiet truth beneath celebrity culture. Fame isn’t a permanent state; it’s a fluctuating signal. Loud, then silent. Focused, then diffuse. It exists only as long as people keep looking. Understanding that doesn’t require cynicism. It requires distance. You can enjoy movies, music, sports, and public figures without confusing visibility for importance. You can appreciate talent without outsourcing meaning. You can follow stories without mistaking them for reality.

Celebrity is not a conspiracy or a scam. It’s a social habit. One that reflects how humans organize attention in a crowded world. It’s not that celebrities don’t matter at all; it’s that they matter far less intrinsically than the system suggests. Celebrity is less about the people on the screen and more about the people watching it. It’s a mirror, not a pedestal. And like most mirrors, it reveals more about the observer than the subject. So the next time a headline insists someone has “broken the internet,” it’s worth pausing. Nothing broke. We just all looked in the same direction at once.