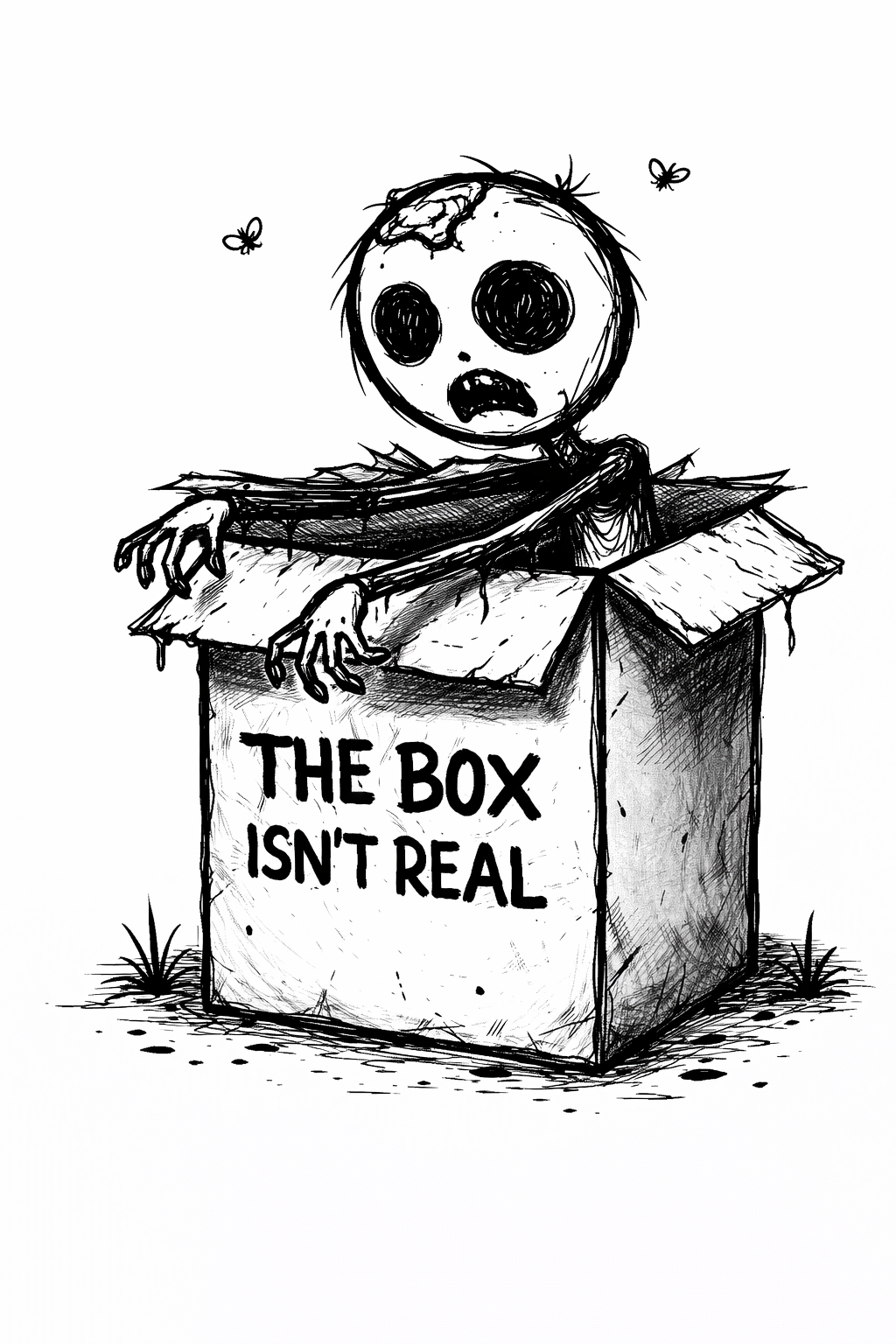

The box isn’t real.

The box people put you in isn’t real. It’s not a physical thing, obviously, but it’s also not a true description of you. It’s a story—an identity summary someone else wrote, usually quickly, based on limited information, and then handed to you like an assignment. “Here,” the world implies, “hold this. Be this. Don’t make it complicated.”

And because most of us are raised to be good citizens of whatever environment we’re in—family, school, community, workplace—we accept it. Not always willingly at first, but eventually. We learn what gets approval. We learn what makes adults less irritated. We learn which version of us is easiest to understand, easiest to manage, easiest to label. Over time, the label stops feeling like something imposed on us and starts feeling like something we are.

That’s the strange part. The box isn’t just a judgment. It becomes a mirror.

It can start early and casually. A teacher tells you you’re a “talker” or “not applying yourself.” A coach decides you’re not athletic enough to invest in. A parent calls you “the responsible one,” “the sensitive one,” “the dramatic one,” as if it’s a permanent job title rather than a mood you had at age nine. A friend group decides you’re the funny one, the smart one, the quiet one, the hot mess, the overachiever. It can be cruel or subtle. Either way, it sticks because it comes with social consequences.

And socially, consequences are everything.

Psychologists describe categorization as a basic cognitive shortcut. Humans simplify complexity by sorting people into manageable concepts: dependable, difficult, charming, lazy, leader, follower. It’s efficient. It reduces uncertainty. It helps a brain that’s trying to survive a busy world avoid having to fully understand every individual it meets. The problem is that efficiency often comes at the cost of accuracy.

Labels rarely capture a whole person. They capture a slice. A behavior someone noticed once. A role you played in a specific environment. A vibe you gave off during one awkward phase of life. The box isn’t truth. It’s a partial impression treated like a conclusion.

And once the conclusion is set, people tend to stop collecting evidence.

What makes the box powerful isn’t that it’s correct. It’s that it becomes reinforced through expectation. This is one of the quiet mechanisms that shapes identity: people treat you as if the label is true, and over time you adapt. You lean into it, resist it, or build your entire personality around proving it wrong. Either way, you’re still responding to it.

This is why labels are rarely harmless. Being told you’re “the smart one” can become pressure. Being told you’re “the funny one” can become performance. Being told you’re “the difficult one” can become isolation. Even positive boxes can trap you. They give you approval, but the approval comes with conditions: keep being that version of yourself.

A lot of people don’t realize how much identity is negotiated. We like to think we simply “are” who we are. But identity is shaped through interaction: who you’re allowed to be, who you’re rewarded for being, and what it costs to be anything else. Humans have a deep biological need to belong, and belonging is often exchanged for compliance. We learn early that being accepted feels safer than being fully expressed.

So we shrink or sharpen ourselves into whatever shape makes sense to others.

Family is often the first place this happens. Most families assign roles without realizing it. Someone becomes “the responsible one.” Someone becomes “the rebel.” Someone becomes “the peacemaker.” Someone becomes “the one we worry about.” These roles aren’t official, but they’re enforced through repetition. If you stray outside your role, people notice. They don’t always punish you, but they react—confused, skeptical, sometimes irritated. The family system likes stability, and stability often means keeping everyone in the part they’ve been cast in.

Children adapt quickly because they have to. When you’re small, approval isn’t just emotional; it’s survival. The people who define you also feed you, house you, protect you. So you internalize the role. You become what you’re called, because being what you’re called keeps things calm.

Then school adds a second layer. Classrooms are built on sorting: grades, tracks, labels, categories. “Gifted.” “Average.” “Troublemaker.” “Quiet.” “Leader.” “Needs improvement.” These labels travel with you, sometimes explicitly, sometimes subtly. Teachers treat you differently based on expectations. Peers follow cues. The label hardens.

This is not because educators are evil. It’s because systems require simplification. But simplification becomes destiny when no one challenges it.

One of the most famous demonstrations of expectation shaping outcomes comes from research on self-fulfilling prophecies in education—often summarized by the idea that when authority figures expect more from someone, that person tends to improve, partly because they receive more attention, encouragement, and opportunities. Expectations change treatment, treatment changes performance, and performance becomes “proof” that the original expectation was right.

In adulthood, the box often becomes more formal. Workplaces don’t just label you; they assign you a role and pay you to stay inside it. Your job title becomes your identity shorthand. You become “Account Manager” or “Designer” or “Operations Lead,” and suddenly your value is measured by how predictably you can perform that function. You’re rewarded for being consistent. You’re penalized for being complicated.

And then we all do something quietly tragic: we start describing ourselves the way systems describe us. We compress our identity into a résumé and a LinkedIn headline. We learn to sound linear. We learn to tell a story that makes sense to strangers. We learn to avoid anything that looks like reinvention, because reinvention looks risky. “We’re looking for someone with a more linear path,” becomes code for “we want you pre-boxed.”

The irony is that humans are not linear. They’re contextual. They evolve. They contradict themselves. They get obsessed with something for a year and then drop it. They grow, regress, change taste, change priorities, have revelations, hit walls, start over. A “linear career path” is not a natural human trait. It’s a corporate preference.

Boxes also persist because they’re economically useful. It’s easier to sell to a category than a person. Once you’ve been segmented—fitness person, tech person, anxious person, minimalist person, luxury person, suburban parent—advertising becomes simpler. Algorithms love boxes because boxes produce predictable behavior. Predictable behavior produces revenue.

This is why identity is constantly marketed back to you. You’re encouraged to “find your brand,” “know your niche,” “be consistent,” “show up as the same version of yourself every day.” Consistency is rewarded online because it’s easier to consume. But in real life, consistency can become another box—one you build yourself and then defend out of habit.

The most unsettling part is that even when you intellectually understand the box isn’t real, it can still shape you. Identity isn’t only a belief; it’s a pattern of behavior reinforced over time. If you’ve spent years being treated like you’re not creative, you may stop attempting creative things. If you’ve been treated like you’re awkward, you may avoid situations that would help you grow socially. If you’ve been treated like you’re “not leadership material,” you may stop raising your hand.

The box becomes internal. At that point, no one needs to keep you in it. You do it for them.

And the box is comfortable, which is why it’s dangerous. Predictability reduces conflict. Staying inside your assigned role keeps other people relaxed. It keeps the world stable. It keeps relationships predictable. It also keeps you smaller than you are.

Most people eventually reach a moment—sometimes quietly, sometimes explosively—where they realize they’ve been living as a simplified version of themselves. The realization can be triggered by burnout, boredom, grief, a move, a breakup, a random hobby, an unexpected interest. Something shifts. You start noticing the gap between who you are and who you’ve been performing.

And the gap hurts.

The discomfort isn’t proof you’re doing something wrong. It’s proof you’re growing. Growth feels like instability because it breaks the agreement you’ve had with the world: “I’ll be predictable, and you’ll accept me.” When you change, other people have to update their understanding of you, and many people resent that. Not because they hate you, but because change creates uncertainty—and uncertainty is mentally expensive.

This is why people sometimes react poorly when you improve. If you quit drinking, someone might tease you. If you start running, someone might roll their eyes. If you start a business, someone might dismiss it. If you get serious about something, someone might call it a phase. It can feel personal, but often it’s defensive. Your growth forces them to see their own stuckness. If you can leave your box, they might have to admit they’re still in theirs.

So what does it actually mean to “escape” the box?

It rarely means announcing it. It rarely means arguing with the people who built it. Boxes aren’t enforced with logic; they’re enforced with social pressure. The way out is quieter and more consistent: you stop playing the part. You allow yourself to be surprising. You become willing to disappoint the version of you that other people preferred.

It helps to practice contradiction. Not recklessly, but honestly. Try something that doesn’t match your established identity. Not because you need to prove anything, but because you’re allowed to. Let your behavior expand. Take up a hobby you have no “brand-aligned” reason to have. Learn something new. Dress differently. Speak differently. Change your mind. You don’t need to justify it with a manifesto.

The simplest phrase in the world becomes the most powerful: “I’m different now.”

Not as an apology. As a fact.

A boxless life isn’t chaos. It’s honesty. It’s refusing to be reduced to a cardboard summary. You are not your job title. You are not your family role. You are not your high school reputation. You are not your worst moment or your best one. You are not a single adjective. You’re a moving target: complicated, contextual, growing.

The box isn’t real. But the time you’ve spent believing it is. The fear you’ve built around it is. The self-doubt it created is. Escaping the box doesn’t erase that history—it just stops it from being your future.

People will say you changed. They’ll say you’re not like you used to be. They’ll say they don’t recognize you.

Good. That means the box is cracking.

And once you see that it was always made up, you don’t have to burn everything down. You just have to stop living inside a story that was never written for the full version of you.