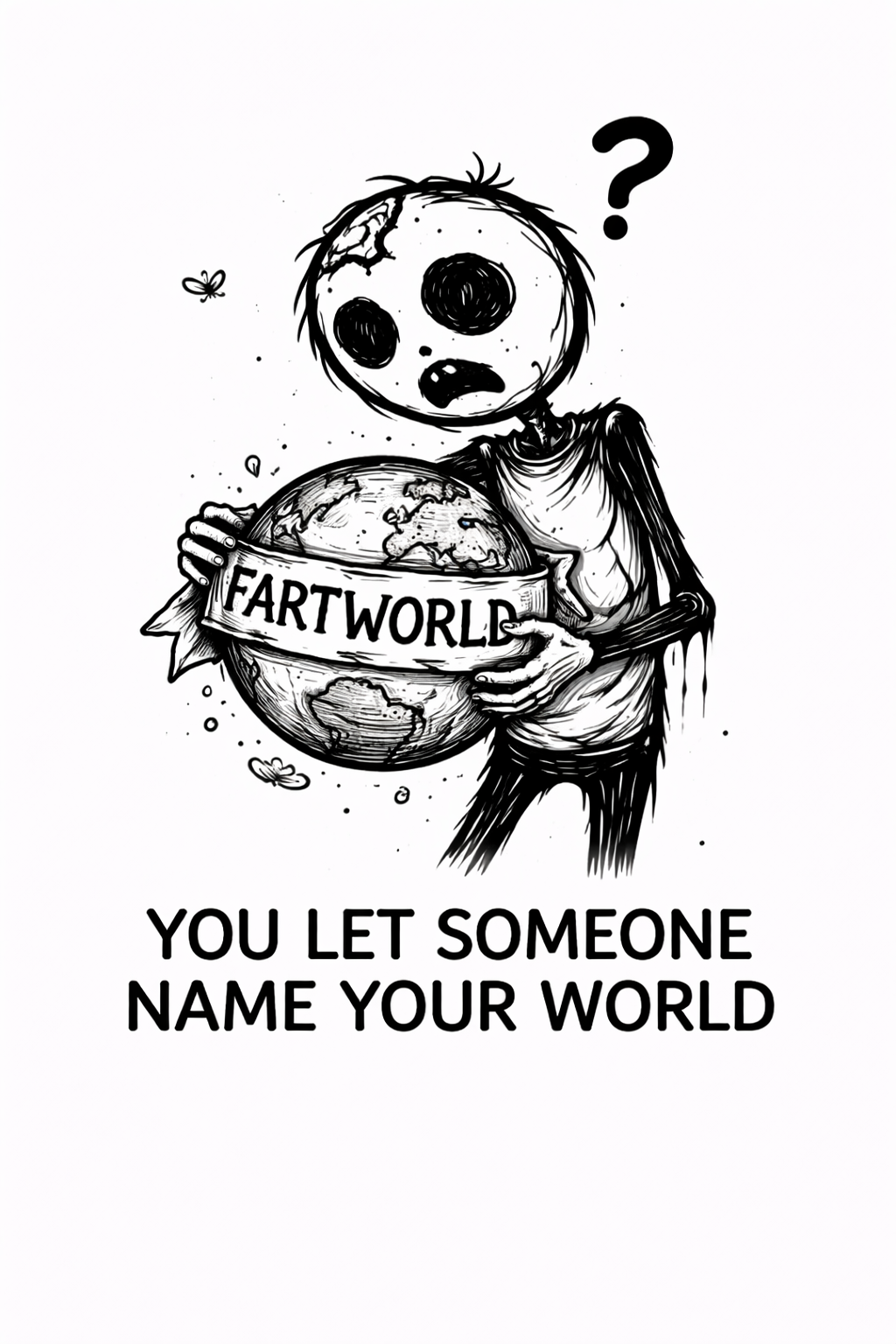

You let someone name your world.

One of the strangest things about being alive is how rarely we stop to notice that everything we interact with has a name, and that not one of those names were inevitable. Every object, every role, every concept you move through daily exists inside a word someone else invented. You look at a chair and think it’s obvious. It isn’t. A chair is a shape doing a job. The sound chair is an agreement. A long-forgotten human once pointed at some arranged materials and assigned a noise to it, and that noise hardened into reality. Now entire civilizations sit on that noise without blinking.

Naming feels natural because it arrives before memory. By the time you’re conscious enough to question the world, the labels are already installed. Language doesn’t wait for consent. It wraps itself around perception and teaches you what counts as a thing before you’ve learned how to doubt. By adulthood, words feel like features of the environment rather than inventions layered on top of it. That’s the trick. You don’t experience reality directly. You experience a labeled version of it. Cognitive scientists like George Lakoff have been pointing this out for decades: language isn’t neutral. It doesn’t merely describe the world, it shapes how the world is perceived. Words carry frames, assumptions, boundaries. They tell you where one thing ends and another begins. They tell you what matters, what’s normal, what’s dangerous, what’s valuable. Whoever names something controls how it’s understood.

Naming isn’t a passive act. It’s an assertion of authority. To name something is to stabilize it, to pin it down, to say “this is what this is.” It turns ambiguity into structure. It makes chaos manageable. And once something is manageable, it can be governed, sold, optimized, punished, celebrated, or ignored. The phrase “the map is not the territory” exists because humans prefer maps. The territory is overwhelming. It’s infinite variation, constant change, and unresolved meaning. Names function as maps. They give us something to hold onto. But once we have the map, we forget it’s a simplification. We start living by it. We mistake the label for the thing. This is how naming becomes power. Take a word like love. It feels universal, almost sacred. People say it as if it’s a shared understanding. But ask a hundred people what love means, and you’ll get a hundred incompatible answers: loyalty, chemistry, safety, desire, obsession, consistency, validation, caretaking, control. The word does not clarify experience, it compresses it. And because the compression feels comforting, we don’t notice how much ambiguity it hides. Someone says “I love you,” and the nervous system reacts as if something precise has been communicated. But it hasn’t. A sound was exchanged. Meaning was assumed. Naming did the rest.

Or take success. Few words have done more damage while pretending to be helpful. Success has no stable definition, yet it’s treated like a measurable destination. Economists, corporations, self-help gurus, and cultures all insert their preferred outcomes into the same word. Wealth. Growth. Recognition. Freedom. Impact. Peace. Visibility. Security. The word stays constant while the meaning shifts underneath it. Because the label remains the same, the illusion of consensus survives. People argue about how to achieve success, not what it actually is. Naming masks disagreement by flattening it into a single term. And this flattening happens everywhere.

Look around the room you’re in. Walls. Windows. Furniture. Devices. Each name feels obvious because you’ve heard it your entire life. But none of those sounds belong to the objects themselves. They’re conventions. You could rename everything tomorrow and the physical reality wouldn’t change, only your relationship to it would. Words feel inevitable because they’re inherited. You didn’t invent the vocabulary you think in. You were handed it fully assembled. Language is scaffolding, not substance. Someone else built it. You just learned to walk inside it. That’s why naming is so deeply entangled with identity. Your name, your legal name, is one of the first labels imposed on you. You didn’t choose it. It was assigned. That sound then followed you into every system you entered: school, work, databases, assumptions. Research has shown repeatedly that names trigger bias. Identical résumés receive different responses depending solely on the name at the top. The label alters the outcome before the content is even read. Your name is not you. But it mediates how you’re perceived. And perception shapes opportunity.

Beyond names, identities themselves are linguistic constructions. “Introvert.” “Leader.” “Creative.” “Difficult.” “High potential.” “Underperformer.” These are not discoveries. They are judgments stabilized into nouns. Once assigned, they begin to act back on the person they describe. People adapt to the label, resist it, internalize it, or organize their lives around disproving it. Either way, the label exerts force. That’s the quiet violence of naming. It simplifies complexity in ways that feel helpful but are rarely accurate. Categorization reduces cognitive load, but it also erases nuance. It trades truth for manageability. Psychological diagnoses, personality types, job titles, demographic buckets, all of them attempt to make the human experience legible. None of them fully succeed. But once named, they’re treated as real. Language doesn’t just describe experience. It constrains it.

That’s the prank at the heart of civilization: we invented labels, believed them, forgot we invented them, and then built systems that punish people for questioning them. Once a word becomes foundational, challenging it feels destabilizing. If you question what “success” means, you’re seen as lazy or lost. If you question what “normal” means, you’re seen as difficult. If you question what “work” or “value” or “productivity” means, you’re treated as naïve. But the instability isn’t in the questioning. It’s in the pretending. Language is not reality. It’s metadata layered on top of reality. But most people never experience the raw data. They experience the interface. They think inside words that were chosen for them. They inherit frames without knowing they’re frames. And this is why renaming things is so powerful.

Cultural change doesn’t start with overthrowing institutions. It starts with redefining terms. When movements succeed, they don’t just change laws, they change language, they change what counts as acceptable. What counts as harmful. What counts as possible. Revolutions are semantic before they are structural. Even on a personal level, renaming alters experience. Cognitive behavioral therapy works largely by reframing, changing the labels attached to thoughts. Acceptance-based therapies teach people to defuse from language itself, to see thoughts as words rather than truths. This isn’t mysticism. It’s linguistics applied to psychology. Rename failure as data, and your nervous system responds differently. Rename heartbreak as transition, and time moves differently. Rename aging as adaptation, and fear loosens its grip. The sensations remain. The story changes. And story is what the brain listens to. That doesn’t mean names don’t matter. It means they matter too much to be left unquestioned.

The future isn’t about finding the “right” words. There are no perfect labels. Every name is an approximation. Every category leaks. The real shift is recognizing that names are arbitrary, and therefore editable. They are costumes, not skin. They can be worn, removed, altered. You don’t have to reject language to see through it. You just have to remember that it’s a tool, not a truth. The world existed before the names. It will exist after them. You are moving through something far stranger and richer than the words you’ve been given for it. Someone named your world. Someone framed your reality. And you’ve been living inside that frame, mistaking it for the view.