That kid isn’t yours

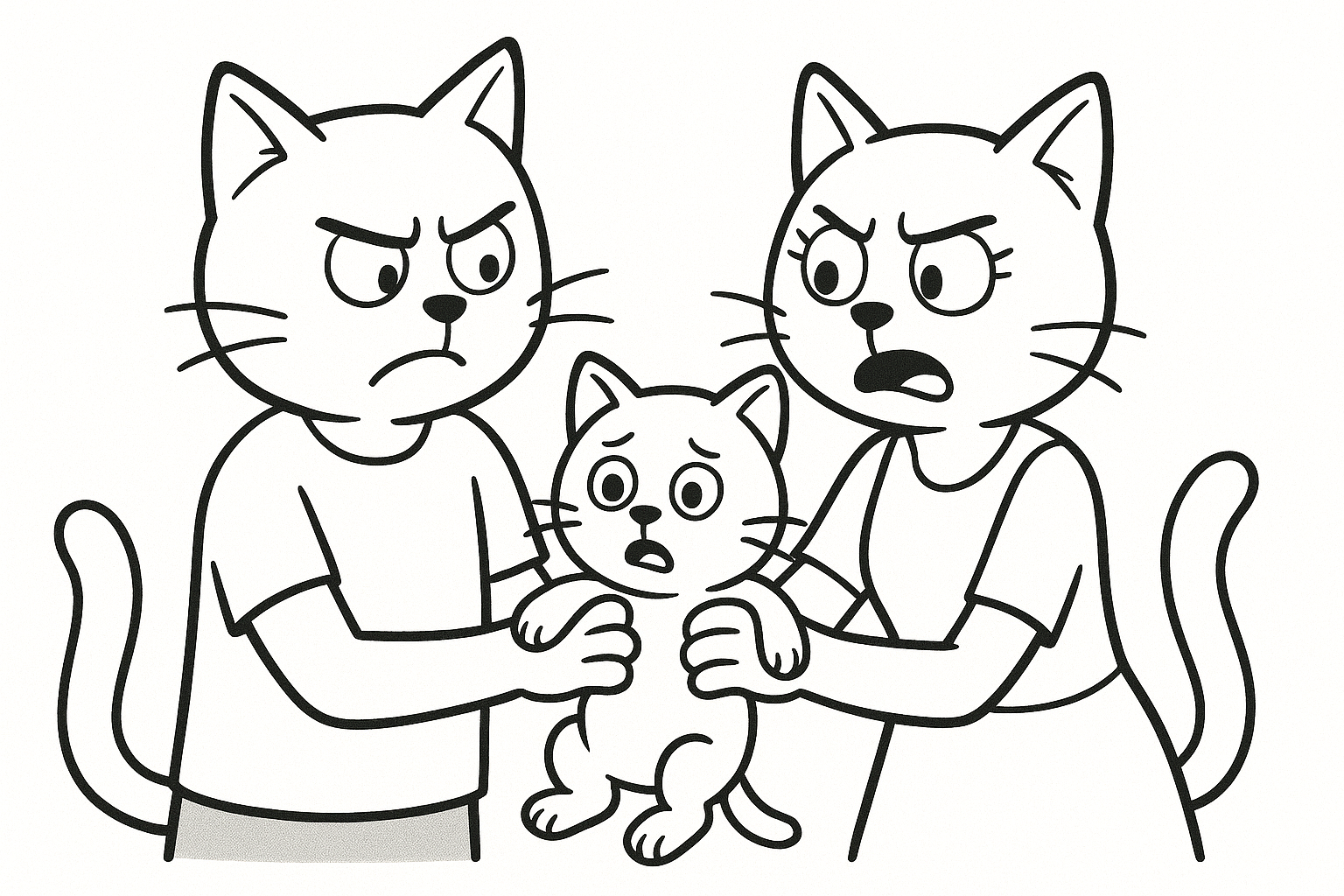

Let’s start with a truth that tends to make parents slightly uncomfortable, especially when they’re already tired: your kids don’t belong to you. Not in the ownership sense, at least. You don’t possess them. You don’t get to control who they become. And despite the emotional, physical, financial, and psychological investment you’ve made, they are not an extension of your identity or a long-term personal project. This can be hard to hear. After all, you carried them, fed them, cleaned up after them, and kept them alive during the phase where they seemed actively committed to their own destruction. You have receipts. You have stories. You have the emotional scars of a family vacation that involved theme parks and poor planning. So yes, the idea that they don’t “belong” to you feels unfair. But it’s also one of the healthiest reframes parenting has to offer.

Yes, you helped make them. That part is undeniable. But creation does not equal ownership. You participated in bringing them into the world, just like flour participates in becoming bread. The bread does not owe the flour its life choices. Once something exists, it becomes its own thing. Children are no different, even when they’re small and need help opening snacks. Kids are not mini versions of you. They’re not do-overs for the things you didn’t finish, didn’t attempt, or quietly regret abandoning. They are not your unrealized dreams wearing sneakers. They are not proof that you “did life right.” They’re not collectibles, trophies, or carefully curated reflections of your values. They are people. Incomplete people, inexperienced people, occasionally unreasonable people, but people nonetheless.

Psychology has been circling this idea for decades. Developmental theorist Robert Kegan described parenting as creating a “holding environment,” a structure that supports growth rather than dictates outcomes. In other words, your role is not to decide who your child should become, but to provide the conditions that allow them to discover that on their own. Safety, consistency, boundaries, encouragement. Not scripts. Similarly, child psychologist Dr. Shefali Tsabary emphasizes that children are not ours to own, shape, or control, but individuals who come through us, not from us. They arrive with their own temperament, wiring, preferences, and limits. Parenting isn’t about installing software; it’s about learning how to live with the operating system they already have. This perspective runs counter to a very modern idea of parenting as optimization. Today, parenting often feels like a performance review. Are you choosing the right schools, the right activities, the right foods, the right language to build the right kind of future adult? The pressure to “get it right” quietly turns children into outcomes. But when kids become outcomes, autonomy becomes a threat instead of a feature.

Historically, the idea that children belong primarily and exclusively to their parents is relatively new. For most of human history, child-rearing was communal. Extended families, neighbors, elders, and entire villages shared responsibility. Kids learned from multiple adults, absorbed different values, and developed identities that weren’t tethered to a single household’s expectations. Anthropologists like Bronisław Malinowski documented societies where communal parenting reduced pressure on individual families and allowed children to develop within a broader social context. In contrast, modern parenting often happens in isolation. Two adults, sometimes one, are expected to meet every emotional, educational, and developmental need while also maintaining careers, relationships, and sanity. Ownership becomes tempting in this context. If you’re doing all the work, it’s easy to feel like you should get control. But control isn’t the reward for effort. It’s usually the opposite of what kids need. Thinking of children as property creates subtle but powerful problems. Ownership implies return on investment. And children are famously terrible investments. You pour time, money, energy, and attention into them and receive very little measurable payoff in return. They don’t appreciate compound interest. They don’t understand sunk costs. They are unimpressed by sacrifice. Gratitude arrives late, inconsistently, and sometimes not at all. If you were expecting acknowledgment, it’s worth remembering that children are not shareholders. They don’t see your effort as extraordinary; they see it as baseline reality. From their perspective, you chose this. They did not. And that distinction matters.

The real work of parenting isn’t shaping; it’s letting go. Slowly, unevenly, and often uncomfortably. Early on, children need you for everything. Then they need you less. Then they need you differently. Then they act like they don’t need you at all, while still quietly depending on you more than they’ll admit. Eventually, if things go well, they need you mostly as a reference point rather than a safety net. This progression can feel like a long emotional exit. Parenting begins with total dependence and moves steadily toward independence. Each stage involves a small loss. First they don’t want help tying their shoes. Then they don’t want you walking them to school. Then they don’t want you asking questions. Then they want your car keys but not your opinions. None of this is personal, though it often feels that way.

The paradox of good parenting is that success looks like being needed less. The goal is not lifelong dependence, even though dependence can feel validating. The goal is to raise someone capable of functioning without you, making decisions without you, and eventually disagreeing with you. If that happens, it doesn’t mean you failed. It means you did your job. Reframing your role helps. You are not the owner. You’re the caretaker, the guide, the temporary scaffolding. You are a launchpad, not the destination. Your responsibility is to provide structure early and space later. To protect without smothering. To guide without steering too hard. To intervene when necessary and step back when possible.

This doesn’t mean disengagement. It doesn’t mean permissiveness or neglect. Boundaries still matter. Safety still matters. Teaching values still matters. But values are not blueprints. They’re tools. Your job is to offer them, not enforce identical outcomes. When children surprise you, by wanting different lives, different identities, different paths, it can feel destabilizing. But surprise is a sign of independence, not betrayal. The moment your child becomes someone you didn’t predict is the moment they become fully themselves.

Ownership would be easier. Ownership would mean clarity, authority, and justification. But parenting was never meant to be easy in that way. It’s meant to be relational, dynamic, and humbling. You are shaping someone who will eventually evaluate you, reinterpret you, and maybe gently disagree with you over dinner years from now. And that’s okay. Parenting isn’t about control. It’s about stewardship. It’s the longest temporary assignment most people will ever take on. You hold responsibility without possession. You invest without guarantees. You guide someone toward a life that is not yours to live.

If that feels unfair, there’s a quiet comfort waiting later. One day, if the cycle continues, your children will have children of their own. And they’ll discover slowly, painfully, and with a lot of coffee, that love does not equal ownership. That care does not grant control. And that raising a human means accepting that they were never really yours to begin with. Just with you for a while.